The Textile Society of the Art Institute under the gui

The Textile Society of the Art Institute under the gui ding hand of Christa C. Thurman produced an un-paralleled tour de force in 2008: The presentation of seventy works that had been part of a 13 year conservation and restoration project of the Art Institute’s unparalleled tapestry collection. Many of these exquisite works were found rolled in the basement, in dire need of repair. All of them were so dirty that the colors were nearly indistinguishable one from another. Christa Thurman took on this daunting labor of love, raised the money, found the laboratory in Belgium and accompanied all the pieces from Chicago and stayed until they were safely home again.

ding hand of Christa C. Thurman produced an un-paralleled tour de force in 2008: The presentation of seventy works that had been part of a 13 year conservation and restoration project of the Art Institute’s unparalleled tapestry collection. Many of these exquisite works were found rolled in the basement, in dire need of repair. All of them were so dirty that the colors were nearly indistinguishable one from another. Christa Thurman took on this daunting labor of love, raised the money, found the laboratory in Belgium and accompanied all the pieces from Chicago and stayed until they were safely home again.

Although it is not known exactly when the first tapestry was produced in Europe, by the early Middle Ages workshops throughout the continent were producing treasured wall hangings for the well to do. In the 14th century suddenly stories were appearing in these weavings instead of simply decorative patterns. Suddenly tapestry was raised to the level of painting. They also had the unique advantage of being very portable, enabling the nobility, clergy and wealthy merchants to take them along on their travels. They acted as room dividers, party decorations and cut the drafts in unheated castles, abbeys and manor houses.

Tapestries were frequently produced in “suites,” a series that allowed the whole story to be told. The golden age of tapestry was 1500 to 1750. The painters who made the designs were usually well known. The master weavers were respected.

Tapestries were frequently produced in “suites,” a series that allowed the whole story to be told. The golden age of tapestry was 1500 to 1750. The painters who made the designs were usually well known. The master weavers were respected.

These manufactories became an economically important factor in their regions and were often tax exempt. A visit to the Gobelins manufactory in Paris makes a fascinating afternoon. The old looms, the size of a large room, are still in use. You can see how the artisans work from behind the tapestry and follow the progress of the weaving with a mirror all the while referring to the cartoon (the full sized desired pattern). The cartoons were valuable in themselves and reused many times.

in their regions and were often tax exempt. A visit to the Gobelins manufactory in Paris makes a fascinating afternoon. The old looms, the size of a large room, are still in use. You can see how the artisans work from behind the tapestry and follow the progress of the weaving with a mirror all the while referring to the cartoon (the full sized desired pattern). The cartoons were valuable in themselves and reused many times.

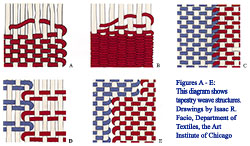

There are two kinds of looms: high warp on which the warps run perpendicularly to the floor and low warp on which the warps are parallel to the floor. On the low warp the cartoon cut into strips would be laid under the tightly stretched strings. On the high warp, the weaver would use a mirror to look behind his seat to the full-sized cartoon hung on the wall.

Tapestries have always been affected by European politics. The Eighty Years War (1568-1648) sent Netherland artisans scurrying to France, England and Italy. During the French Revolution (1789-1799) many of the tapestries were either defaced or destroyed to retrieve the gold from the threads, not to mention destroying the symbols of monarchy and nobility.

The mechanized culture of the Industrial Revolution led to the near demise of this hand-labor intensive art form. However, William Morris established a tapestry workshop at Merton Abbey to combat the “soul-lessness of art” this mechanization encouraged.

The mechanized culture of the Industrial Revolution led to the near demise of this hand-labor intensive art form. However, William Morris established a tapestry workshop at Merton Abbey to combat the “soul-lessness of art” this mechanization encouraged.

Chemical dyes, synthetic and analine, were not invented until late into the 19th century. The radiant, luminous, exuberant colors in these tapestries were produced by woad and indigo for the blues; mustard gave the yellows; Red in all its glory was produced from brazilwood, the cochineal insect and madder. The lustrous beauties of the colors after they had been cleaned was really indescribable.

Tapestries are only recently beginning to be taken seriously as works of art, not merely desirable decoration. When Mrs. Thurman graciously took the Textile Society on a personal tour with anecdotes, the gasps were audible as she described how this or that work was cut to go around doorways or fit into a particular space or go behind a particular chest. The modern mind boggles at the lack of respect for both art and craft. Like so much that comes from human hands working long and carefully, we seem to be able to value it the more, the farther away we go.

Many thanks to Mary Ann Crotty and Ryan Paveza.

The Divine Art: 400 Years of European Tapestries

Posted in Uncategorized.